The Miscellany: The Munich Shakespeare Library Blog

Forging Shakespeare in the Eighteenth Century: The Confessions of William Henry Ireland

The closing decade of the eighteenth century was a boom period for Shakespeare in Britain. The preceding decades had seen a steadily growing interest in his life and work. Scholars had painstakingly edited and commented the texts of his poems and plays; actors like David Garrick had revived Shakespeare on stage; and a lavish jubilee celebration held at Stratford-upon-Avon had helped to canonize the author as a national saint. But such literary idolatry lacked a solid biographical basis. Much about Shakespeare’s life remained shrouded in mystery – which in turn fuelled speculation about the existence of undiscovered manuscripts that might help to solve the puzzle. At this point, a young law clerk entered the scene. In late 1794, William Henry Ireland, not yet twenty at the time, began producing a series of Shakespeare forgeries which he presented as lost manuscripts in the author’s own hand. Ireland started with fake signatures and shorter documents, but as he became more confident in his ability to mimic Shakespeare’s handwriting and style, he began to produce longer works, culminating in the manuscript of a whole play, Vortigern and Rowena, which he passed off as a long-lost authentic Shakespearean masterpiece. Ireland’s fabrications were eventually exposed in 1796, but the young fraudster was keen to capitalize on the affair.

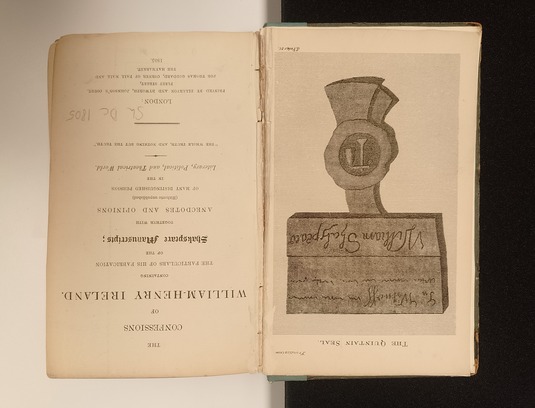

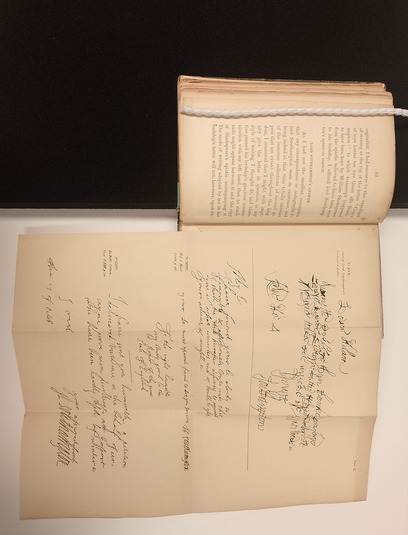

In 1805, a decade after the scandal, Ireland published a volume of Confessions (the Shakespeare Research Library owns a copy of the first edition). The book is something of a self-serving memoir whose main aim is to explain and justify Ireland’s forgeries. Ireland begins by recounting his personal journey, which features an account of his early obsession with Shakespeare – something that ran in the family. William Henry’s father, Samuel Ireland, was a passionate admirer of Shakespeare and had long hoped for the discovery of new manuscripts. His son was ready to oblige and to fill the void. In line with his later book’s catchy title, Ireland promises to conceal nothing. He openly admits to creating the fake documents in question; but he also persistently defends his actions, claiming that his intention had never been to deceive but rather to revive Shakespeare and kindle enthusiasm about his work. One of the many striking features of the book are Ireland’s technical explanations of how exactly he went about producing his forgeries (finding old paper, mixing his own ink, imitating Elizabethan handwriting, artificially ageing documents). This is rendered tangible through illustrations and foldouts which are included in the volume.

The Confessions reveal Ireland’s internal conflict. He expresses guilt over the deceit but insists that it was motivated by a genuine love for Shakespeare and his works. By the end of the book, Ireland acknowledges the harm caused by the forgeries, but his narrative paints him as a misguided amateur rather than as a hardened criminal. The book is hence less a confession than an apology. Ireland describes himself as a sinner, but he ultimately does not truly repent. His Confessions offer not only a personal account of a literary forgery but also a reflection of the intense cult of Shakespeare that flourished in late eighteenth-century Britain. The book sheds light on Ireland’s contemporaries’ often desperate desire to unearth more of Shakespeare’s works and to collect further documentary evidence about his life. The Confessions are a fascinating historical document that reveals the complex relationship between authorship and authenticity in a period that was deeply invested in the idea of Shakespeare as a cultural icon.

Tim Sommer

-

Archive

- The First Folio of Shakespeare

- Raphael Holinshed's "Historie of Scotlande"

- Holinshed’s Historie of Scotlande & William Shakespeare’s Macbeth

- The Fairy World in Watercolour and Ink

- Margaret Cavendish "The Blazing World"

- Lisa Jardine "Still Harping on Daughters: Women and Drama in the Age of Shakespeare"

- Stephen Greenblatt "Shakesperean Negotiations"

- Hedwig Schwarz and her German translations

- Paul Edmondson and Stanley Wells "All the Sonnets of Shakespeare"

- Heinrich Heine "Shakespeares Mädchen und Frauen"

- The Tempest, illustrated by Edmund Dulac

- David Garrick's edition of "Romeo and Juliet"

- Double Falsehood

- Arden of Feversham