Holinshed’s Historie of Scotlande & William Shakespeare’s Macbeth

Raphael Holinshed’s Historie of Scotlande & William Shakespeare’s Macbeth

Not only is Holinshed’s Historie of Scotlande (1577) a major part of Tudor historiography, it is also of immense value to readers and researchers as a source text for William Shakespeare and his contemporaries. The Chronicles gave rise to more plays than any other historiographical work of its time and there is an impressive range of dramatic genres and literary adaptations that have emerged from Holinshed’s work. Shakespeare probably used the second edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles (1587) as a key source for his English history plays (for instance to write Richard III and Henry V) as well as an inspiration for Cymbeline and King Lear.

Holinshed’s Historie of Scotlande was an important source text for Shakespeare’s Macbeth (c. 1606-1607). It allowed Shakespeare to engage with the history of Scotland at a point in time when, following the death of Elizabeth I., England had become a nation ruled by a Scottish Stuart King. Shakespeare’s adaptation of stories found in Holinshed’s Historie are therefore not only a source of creative inspiration, but a way of facing pressing political questions through the lens of history.

Shakespeare’s Macbeth presents a fascinating engagement with Holinshed’s historiography and a creative rewriting of Holinshed’s account of different events and time periods. Macbeth draws on at least two periods of medieval Scottish history that are portrayed separately by Holinshed: the reign and murder of King Dubh (sometimes also spelled as “Duff”, who ruled Scotland from about 962 to 967 AD; see 1577: pp. 206-209) and the reign and assassination of King Duncan (who ruled from about 1034 to 1040 AD; see 1577: pp. 239-252). Shakespeare takes events from these two periods and merges them together to weave the plot for Macbeth.

Especially the portrayal of Lady Macbeth and the three “weird sisters” or witches in Shakespeare’s play draws on Dubh’s and Duncan’s stories in Holinshed. In Holinshed’s account of the short reign of Dubh, one of his nobles, Donwald, becomes dissatisfied with the King’s rule and is persuaded by his wife to act on his feelings of frustration and anger:

“She … counselled him … to make him away and shewed him the meanes whereby he might accomplishe it. Donwalde thus being the more kindled in wrath by the words of his wife, determined to follow hyr advice in the execution of so haynous an acte.”

(1577: p. 208)

Donwald and his wife plot to kill Dubh: they organise a banquet and make his chamberlains drunk, so that the King’s murder can be committed without witnesses or interruption. These events are echoed in Act II of Shakespeare’s play, when Macbeth and Lady Macbeth devise their plan to assassinate King Duncan. Lady Macbeth and Donwald’s wife are framed as women with considerable influence over their husbands and become the instigators of regicide. Although Shakespeare gives a much greater role to Lady Macbeth, Holinshed’s text, through further annotations in the margins, already draws special attention to the events as a consequence of female influence: “The womans evill counsell is followed” (1577: p. 208).

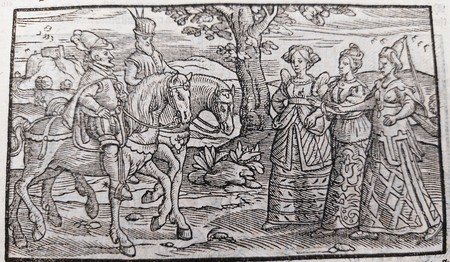

Shakespeare also drew substantially on Holinshed’s account of the reign of King Duncan, especially when Macbeth and Banquo encounter three women who prophesy that Macbeth will be King of Scotland:

“It fortuned as Makbeth and Banquho journied towards Fores, where the king as then lay, they went sporting by the way togither without other companie, save only themselves, passing through the woodes and fieldes, when sudenly in the middes of a laund, there met them three women in straunge and ferly apparell, resembling creatures of an elder worlde, whom when they attentively behelde, wondering much at the sight, the first of them spake and sayde; All hayle Makbeth, Thane of Glammis (for he had lately entred into that dignitie and office by the death of his father Synel.) The second of them said: Hayle Makbeth thane of Cawder: but the third sayde; All hayle Makbeth that hereafter shall be king of Scotland.”

(1577: p. 243)

Holinshed’s text, like Shakespeare’s, gives these three women immense power as it is their prophecy which sets the following events into motion. However, Holinshed’s text describes the women as dressed in “strange and ferly apparel” (“ferly” meant wondrous or unexpected) and Macbeth and Banquo initially do not believe their eyes. The encounter appears to them as a “fantasticall illusion”.

The three women are presented variously as “creatures of an elder worlde”, “weird sisters or feiries”, and as “Goddesses of destinie, or els some Nymphes or Feiries, endewed with knowledge of prophesie by their nicromanticall science” (1577: p. 244). Holinshed’s text does not, in fact, call them witches. The phrase “weird sisters” is taken up by Shakespeare in the women’s first encounter with Macbeth (although, in the First Folio edition of 1623, the women are called the “weyward sisters”):

ALL: The Weïrd Sisters, hand in hand,

Posters of the sea and land,

Thus do go about, about,

Thrice to thine and thrice to mine

And thrice again, to make up nine.

Peace, the charm’s wound up.

(Macbeth, 1.3.33-38)

Interweaving elements of the story of King Duff with an account of King Duncan’s assassination by Macbeth, Shakespeare constructs an entirely new vision of events for his play.

Lara Ehrenfried