Hedwig Schwarz and her German translations

Hedwig Schwarz & Her German translations of Coriolanus (1945) and Much Ado about Nothing (1944)

The Munich Shakespeare Library holds two valuable typescripts by the German translator and author Hedwig Schwarz, whose translations of Coriolanus and Much Ado about Nothing are a unique source for studying twentieth-century translations of Shakespeare as well as dramaturgical rewritings of Shakespearean material for German-speaking readers, actors, and audiences.

title page of Hedwig Schwarz' translation of Coriolanus

(Munich Shakespeare Library)

Schwarz herself wrote an essay about her work as a translator of Shakespeare’s plays in 1956. In this essay, she criticizes the practice of word-for-word translation which, in her opinion, often affects the performability or playability of a work in a different language. To Schwarz, translating Shakespeare requires a “quick wit” (“Schlagfertigkeit”), spontaneity, and a nuanced approach to theatre and the realities of performing on stage. “Bühnenwirksamkeit” (179) – both the effect and effectiveness of staging – is a key word which recurs throughout her writing on theatre and translation. To render the dramatic text “bühnenwirksam” is to make it both effective and effectful on stage for actors and audiences alike.

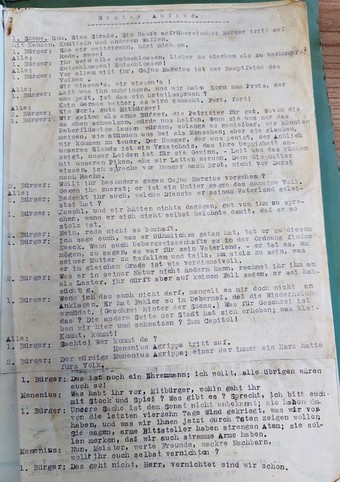

typescripts of Hedwig Schwarz' translation of Coriolanus and Much Ado about Nothing (Munich Shakespeare Library)

As part of her work as a translator, Schwarz recognises that it is necessary to transfer some of Shakespeare’s stylistic characteristics into German:

„sprachliche Dichte, Fülle der Bilder und Metaphern, barocke Antithesen, unerschöpflich sprudelnde Wortspiele und die so häufig überraschende Wendung einer bildlich gemeinten Redensart oder eines Sprichwortes ins Konkrete.“ (176)

[rhetorical and linguistic density, a richness of images and metaphors, the use of baroque anti-thesis, inexhaustible puns and the often surprising turn of abstract or figurative idioms into literal concreteness.]

However, all of these features also need careful balancing so that they do not overwhelm or deter modern audiences. Schwarz wants to do justice to the text on three counts: she wants to do justice to the style and spirit of Shakespeare’s “genius” (183), but also to the requirements of the modern stage and modern audiences. Her approach to Shakespeare, then, is perhaps best described in her own words as “Bearbeitung” rather than “Übersetzung”. In other words, Schwarz sees her work as dramaturgical editing, rather than as a mere translation. This also means that her work often uses underlying structures and key points of Shakespeare’s dialogue, but rewrites scenes loosely around these guiding principles. Her style and choice of words often modernizes the text to increase its accessibility for audiences and readers. Compare, for instance, her translation of Coriolanus’s speech in 5.3.46-59 with Shakespeare’s original:

Coriolan: Wie ein blöder Spieler

Vergaß die Rolle ich, bin aus dem Text

bis zur Beschämung gar. Mein beßres Ich,

vergib mir meine Härte, doch sag darum

nun nicht: „Vergib den Römern.“ – O, ein Kuß,

wie mein Verbanntsein lang, mein Rächen süß!

Nun, bei der eifersüchtigen Herrscherin

des Himmels, diesen Kuß nahm ich von dir,

Geliebte, mit, und meine treue Lippe

bewahrte keusch seitdem ihn. – Götter, ihr!

Ich schwatz, und aller Mütter edelste

bleibt unbegrüßt. Sink, Knie, in die Erde! (er kniet nieder)

Von deiner Ehrfurcht zeige tiefern Eindruck

Als das von Söhnen sonst.

Coriolanus: Like a dull actor now,

I have forgot my part, and I am out,

Even to a full disgrace. Best of my flesh,

Forgive my tyranny, but do not say

For that “Forgive our Romans.” (They kiss.)

O, a kiss

Long as my exile, sweet as my revenge!

Now, by the jealous queen of heaven, that kiss

I carried from thee, dear, and my true lip

Hath virgined it e’er since. You gods! I prate

And the most noble mother of the world

Leave unsaluted. Sink, my knee, i’ th’ earth; Kneels.

Of thy deep duty more impression show

Than that of common sons.

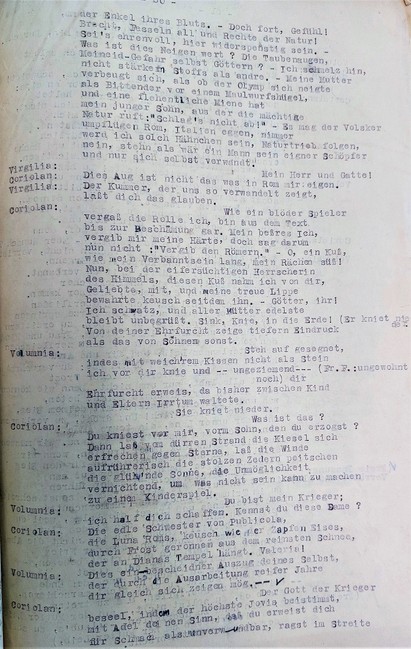

typescript of Hedwig Schwarz' translation of Coriolanus, Act 5, Scene 3

(Munich Shakespeare Library)

Schwarz selects a number of words and expressions that appear to have been chosen for their contemporary usage in spoken German. She translates “dull actor” as “blöder Spieler”, which, strictly speaking, does not capture the literal sense of the expression, but presents audiences with a modernised approximation. Key words that also serve to characterise Coriolanus, giving audiences a taste of his personality, (“tyranny” and “duty”) are translated as “Härte” (harshness) and “Ehrfurcht” (awe or reverence). Again, these terms appear not quite right if the translator were to aim for a literal transfer of meaning – however, these words are suited for giving readers and audiences an impression of Coriolanus’s character whilst also appearing more modern and idiomatic within the flow of modern, spoken German (both are also dissyllabic, which made it easier for Schwarz to achieve a transfer of the Shakespearean meter). The German “Ehrfurcht”, more strongly than the English “duty”, also underscores Coriolanus’s unconditional reverence for his mother. The translation of “exile” as “Verbanntsein” (being banished) makes an interesting linguistic point about Coriolanus’s fate and his hand in it: “Verbanntsein” focuses the listener’s attention to the state of having-been-banished and frames Coriolanus as the subject of unforgiving treatment by the Romans.

Ultimately, it is Schwarz’s own „Probe auf Bühnenwirksamkeit“ (179), her critical self-reflection and evaluation of the text’s effect and effectiveness on stage, that determines her work as a translator and editor. Her typescripts give readers and researchers an intriguing insight into her approach to reading, writing, and staging Shakespeare for German-speaking audiences.

Suggested Reading:

Ewald Mengel. 1993. „Der fromme Seeräuber, der aufs Meer schiffte“: Vom Umgang deutscher Übersetzer mit Shakespeares komischen Wortspielen“. Europäische Komödie im Übersetzerischen Transfer. Eds. Fritz Paul, Wolfgang Ranke, Brigitte Schultze. Tübingen: Gunter Narr. 325-344.

Hedwig Schwarz. 1956. „Arbeit für Shakespeare durch Shakespeare-Bearbeitungen“, in: Shakespeare-Jahrbuch, Bd. 92, 175-183.