Raphael Holinshed's "Historie of Scotlande"

Raphael Holinshed’s "Historie of Scotlande" (1577)

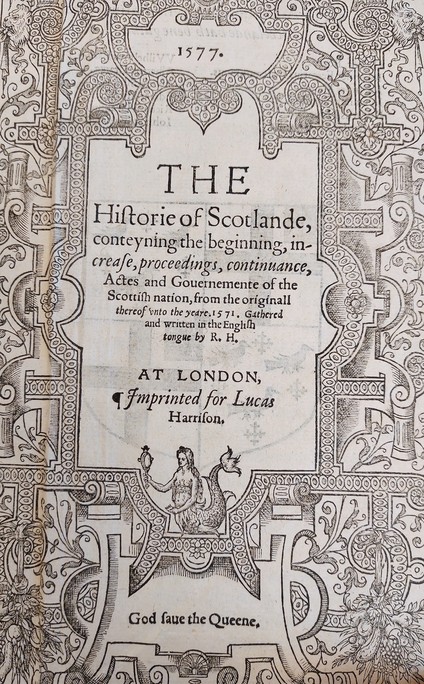

The Shakespeare Research Library holds many wonderful resources that allow readers to delve deeper into Early Modern England and its literature, history, and culture. One of the key holdings of the library is a carefully preserved first edition of Raphael Holinshed’s Historie of Scotlande (1577). This book is part of a larger, multi-volume work which chronicles the histories of England, Scotland, and Ireland from the early stages of human settlement to the second half of the sixteenth century. The stories of the three nations are told separately and illustrated with woodcuts that were commissioned especially for the work by Holinshed and his collaborators.

Holinshed himself was probably from Cheshire and came to the project of the Chronicles at the request of the London-based bookseller and printer Reginald Wolfe. Upon Wolfe’s death in 1573, Holinshed took over the project, supported by at least eight other writers.

Holinshed’s Chronicles (and, as such, his Historie of Scotlande) follows a larger tradition of history writing in Britain that included Nennius’s Historia Brittonum (circa 830 AD), Bede’s Ecclesiastical History (731 AD) and Robert Fabyan’s New Cronycles of Englande and of France (1516). In the Early Modern period, to create a chronicle meant to gather information and to order it; to collate important events and to present them as stories in chronological succession.

During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558-1603), Holinshed’s Chronicles were planned and compiled for multiple reasons. The printing of history books had become a lucrative business following the introduction of the printing press to England by William Caxton in the 1470s. However, an increasing demand for printed books was only one reason for Wolfe and Holinshed to take on the venture of the Chronicles. As Henry VIII had instigated the English Reformation, political and private attention refocused from the European continent to Britain’s own history in the decades after this event. Holinshed’s Chronicles are therefore not simply a collection of anecdotes about the histories of England, Scotland, and Ireland, but an important testament to the way in which the status quo of 1577 could be read, interpreted, and, at times, justified through a curated narrative of the past.

The Historie of Scotlande begins with a literal scene-setting: a description of Scotland and a survey of its lands, followed by a list of its dukedoms and earldoms. The description of Scotland provides spatial orientation for the history of the nation that follows in a loose chronological structure. It starts with the early settlement of Scotland and a narrative of the ancestry of its people. The first edition of 1577 ends with the fall of Mary, Queen of Scots, and her son’s accession to the throne as James VI of Scotland.

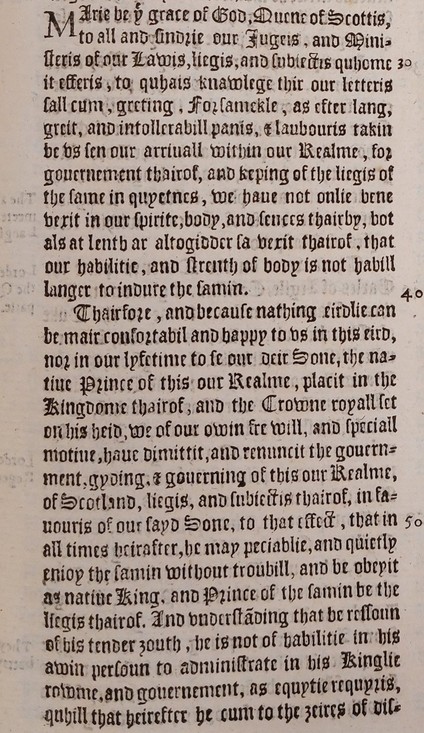

The representation of Mary is particularly fascinating in this first edition, which was printed a mere ten years before Mary’s execution at Fotheringhay Castle. While, generally, the account of Scotland and its rulers presented in the Chronicles takes care and time to unfold action and character, it is noteworthy how, by comparison, the story of Mary is kept very brief (presumably because Holinshed is dealing here with very recent political events). Mary’s decision to abdicate and pass on the crown to her son James is framed as a voluntary decision by the text. Holinshed and his collaborators even include three letters, signed by Mary, which seem to leave little doubt about her intentions:

“nothing eardlie can be mair confortabil and happy to us in this eird, nor in our lyfetime, to see our deir Sone, the native Prince of this our Realme, placit in the Kingdome thairof, and the Crowne royall set on his heid, We of our own free Will, and special motive, have dimissit and renuncit the government” (1577: p. 507).

As the letters suggest that Mary willingly surrendered her right to rule Scotland, the reader may be surprised to witness on the following page that she is, in fact, detained and kept prisoner at Lochlevin Castle until her escape is facilitated “by the means and helpe of George Douglas” (1577: p. 508). It is only by implication that the reader is invited to reflect on the circumstances of Mary’s abdication and that it may have been the result of coercion rather than volition.

The value of Holinshed’s Historie of Scotlande for readers and researchers today lies in the kind of history it presents, but also in the style and structure in which this history is transmitted to us. It is a key text of Tudor historiography that is enormously rewarding to read as it offers unique insights into ideas of nation-making and national history in Early Modern England.

Lara Ehrenfried